Angle

Sponsored by TypeMates . Typefaces in use: Edie & Eddie Modern , designed by Lisa Fischbach, 2022.

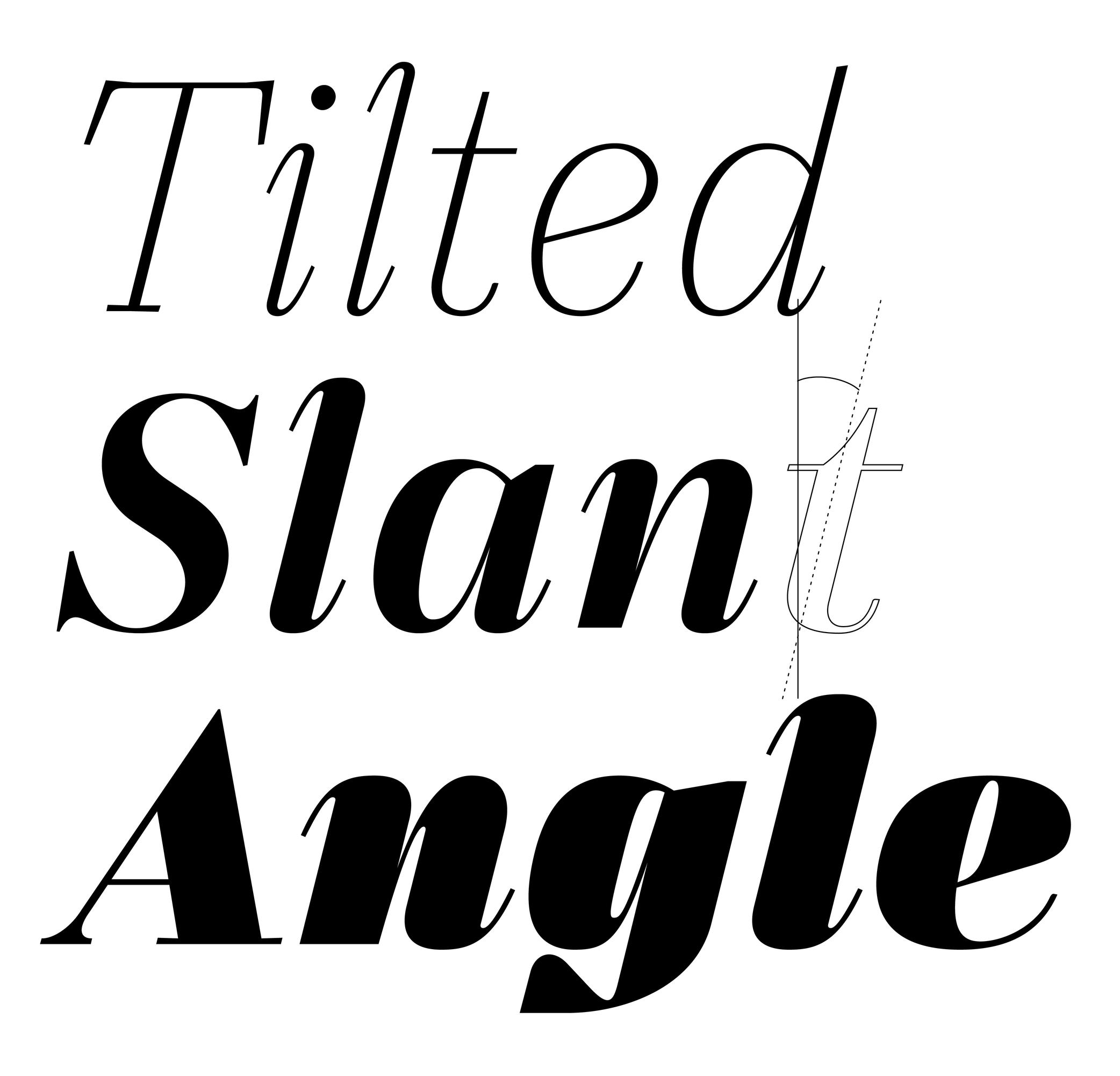

(Read More)Also called slant.

The angle is what we can observe on italic-style letterforms. We say the vertical stems are stretched and leaning to the right at a certain angle.

In the same typeface family, the degree of the italic angle may vary from one weight to another, different sizes of use (display to caption styles), different scripts, or even from one glyph to another in the same style to optically improve the typeface’s balance.

Axis (in Type Design)

Sponsored by R-Typography . Typeface in use: Gliko Modern L , designed by Rui Abreu, 2018.

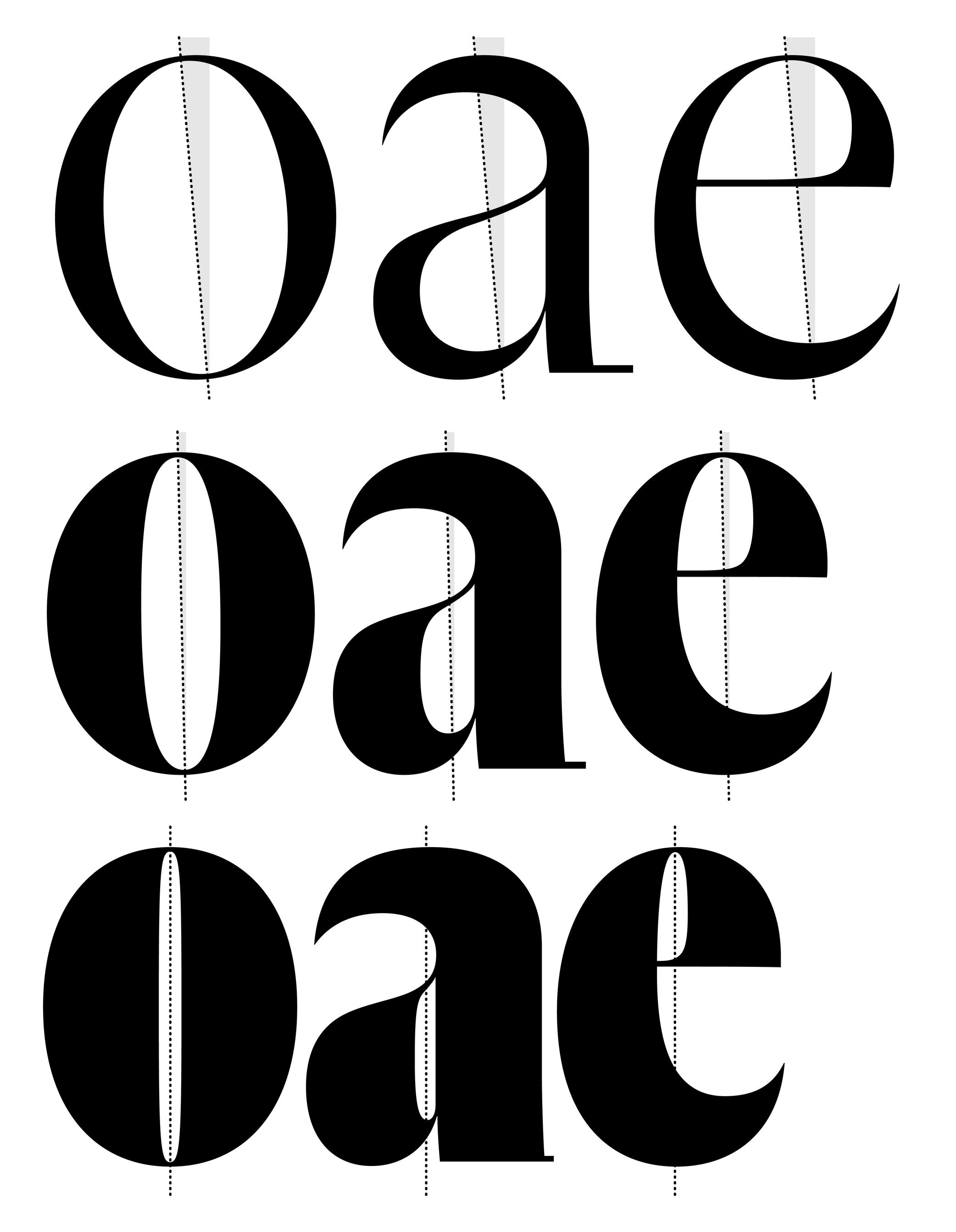

(Read More)In Latin script, we speak of a “diagonal,” “tilted” or “oblique” axis when we refer to the shapes of letters in a typeface that have some contrast.

In calligraphy (when using a broad nib pen), the axis of the stroke is defined by the angle at which the pen is held, from which a contrast between thin and thick parts is formed. The axis should be kept the same (or very similar) for a consistent construction on all glyphs.

Body Text

Sponsored by TypeTogether . Typeface in use: Aneto , lead designers: Veronika Burian, José Scaglione, 2022.

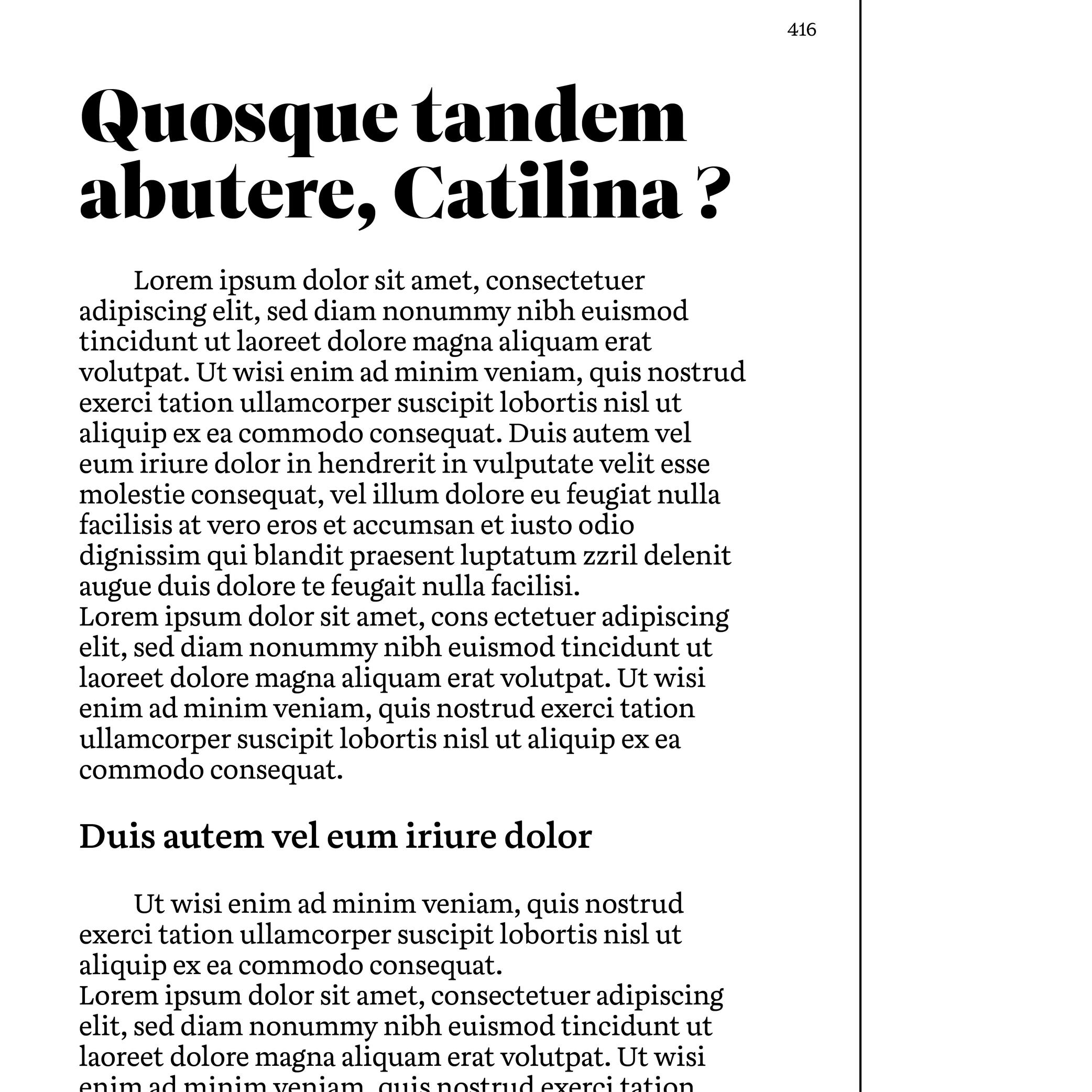

(Read More)Also called body copy or running text, body text is usually the main written part of a document. Titles, subtitles, captions and others should be visually different from the body text so each type of information is clearly distinct and recognizable.

It is advised to set the body text at a size that is most comfortable for long reading: from 9 to 12 points for printed media and 16 to 18 points for digital screens.

Bold (weight)

(Read More)

(Read More)While Regular is the most common weight for body text, Bold is a style often chosen to highlight a word or a sentence with a stronger emphasis than Italic.

Calligraphy

Illustration: Jonny Wan .

(Read More)The word calligraphy comes from the Greek kalos, meaning “beautiful,” and graphein, meaning “to write.” Together, it means “to write beautifully.”

Many civilizations around the world have practiced calligraphy (and continue to do so today) using a variety of tools: brush, pen, quill, broad nib pen or brush, etc. Most even consider it to be an art form.

Today, we describe typefaces whose letters and characters are inspired by those written with a calligraphy tool and following certain calligraphy styles as calligraphic. However, this is slightly different from “script” or “handwritten” styles, as those refer to handwritten shapes free from any particular calligraphic style.

Caption

(Read More)

(Read More)To inform a reader that a passage of text is a caption, it is usually placed near the image it is linked to, but it is usually also set in a smaller size and/or in a different style.

Some typefaces contain a specific caption style in the family with optimized details for specific use in small sizes, such as lower contrast and higher x-height.

Center Space

Sponsored by Mallikātype . Typeface in use: Nan Sans, designed by Tianmeng Xue. Coming soon.

(Read More)In the Chinese Hanzi script, the center space (or optical core, 中宫 in Chinese) corresponds to the central area of a character, similar in Latin to the area between the x-height and the baseline. This area can differ from style to style, but it has to be visually constant for all characters in a typeface.

A text typeface with a bigger center space has its legibility improved for small sizes.

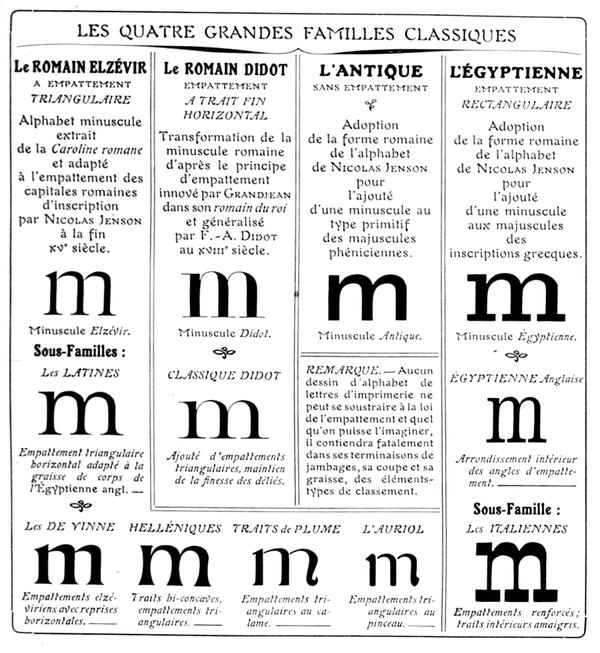

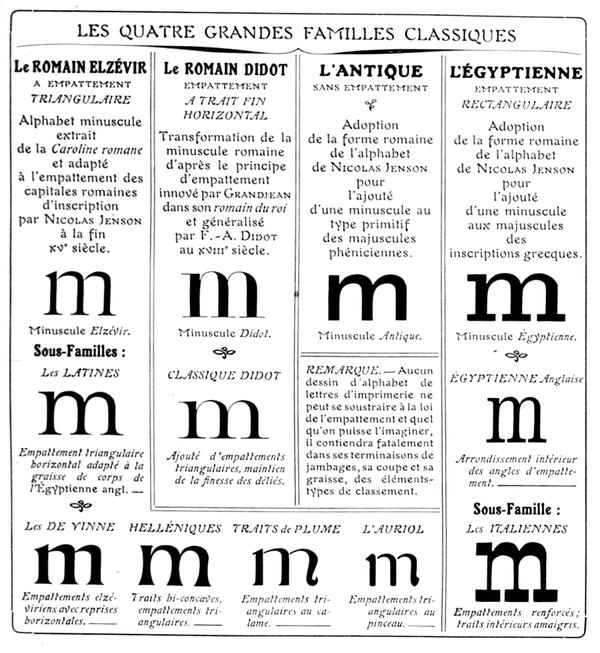

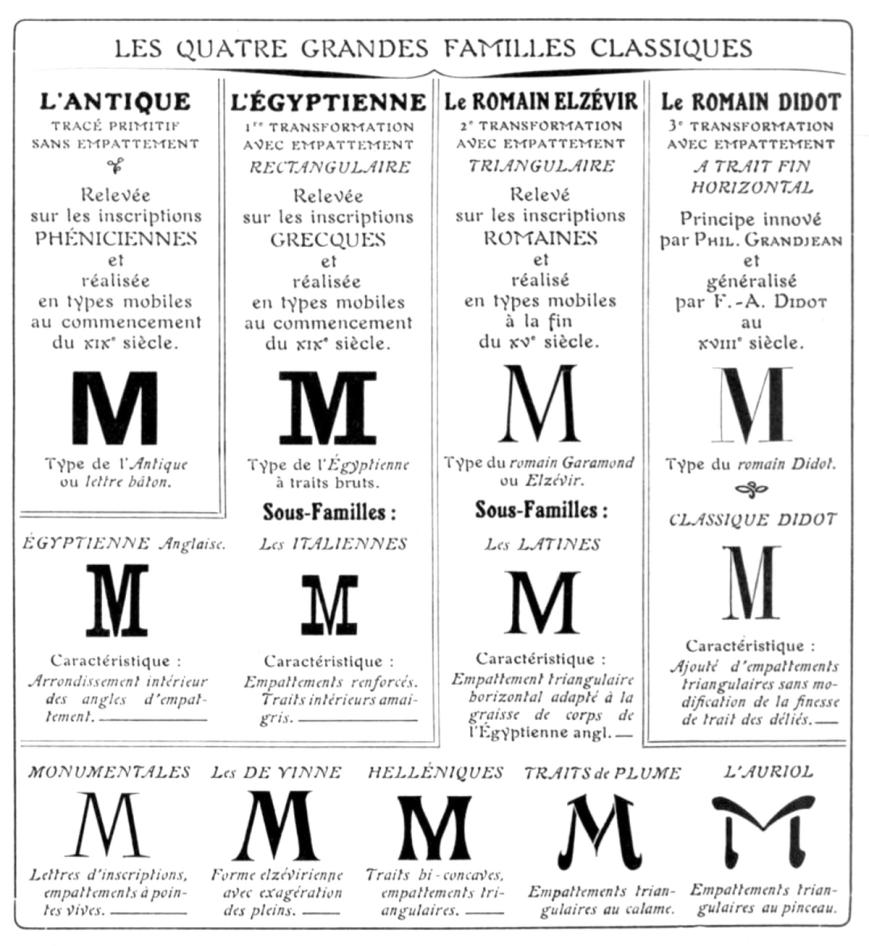

Classification

Francis Thibaudeau’s typographic classification, from Manuel français de typographie moderne, Francis Thibaudeau, 1924. Collection of Bibliothèque nationale de France (French National Library).

(Read More)With the many styles and designs of typefaces that exist, it can be difficult to describe, sort, or even find them in a catalog that isn’t familiar to the user.

Each writing system has its own typeface classification categories that best suit its nature and history. As aesthetic values differ from one culture to another, the same (or similar) style may not convey the same impression across different scripts, and one category considered a convention for one script is not always relevant to others.

For example, Latin typefaces have been sorted into multiple classification systems since the beginning of metal typesetting. Here are some of them:

• Thibaudeau, by French typographer Francis Thibaudeau in 1921, with four categories: Elzévirs, Didots, Égyptiennes and Antiques;

• Vox (or Vox-Thibaudeau), by French historian Maximilien Vox in 1954, who started with the Thibaudeau classification as a basis and added more categories to include the additional typeface styles in the Deberny & Peignot type foundry’s library;

• Vox-ATypI, with additional categories and subcategories from the ATypI (Association Typographique Internationale), added between 1962 and 2021.Today, classification systems vary from one type foundry to another, using more or less “standardized” terms better suited to their own catalog or the scripts covered. These boxes also help users find what they are looking for in a wide variety of choices. They are not rules to be followed to the letter. Imagination and creativity shouldn’t be confined!

Custom

Illustration: James Graham .

(Read More)Companies, brands, institutions and so on can find great benefits in using and/or owning a custom-made typeface with a design that fits their voice. Unlike retail typefaces, they can be used as an important and exclusive element of the visual identity and be fully suited to their needs.

A custom typeface costs more at first than a license of an existing retail one (the client can have a design for their exclusive use instead of a retail design that may be used by many others). Still, it can be financially and strategically more interesting, and profitable than licensing retail typefaces in the long run. The pros and cons between these choices are worth the effort of comparison and evaluation.

Display

(Read More)

(Read More)Display (or Titling) typefaces are designed and used at large sizes to catch the reader’s attention (in posters, billboards, newspaper or magazine titles, covers, etc.).

In order to do so, they have more elaborate designs and/or exaggerated details than typefaces for running text.

Expansion

(Read More)Expansion is one of the multiple contrast types in Latin-script type design (along with translation and rotation).

The specificities of the expansion contrast come from the pressure applied while writing a stroke with a fountain pen or quill (the two flexible tips split with added pressure) while keeping the pen tip at a vertical axis.

Bodoni and Didone (or Didot) styles are typical examples of expansion contrast typefaces.

Geometric

(Read More)

(Read More)A typeface with a geometric style has shapes designed in a way that follows the logic of geometry (straight, round, square, etc.).

But our human eyes are organic (as opposed to artificial), we need to use optical tweaks and adjustments in addition to the shapes drawn out of geometric tools to make the letterforms look geometric.Handwriting

Illustration: Yann Bastard .

(Read More)The word ‘handwriting’ refers to texts written by hand.

Handwritten forms of any languages, combined together as handwritings, are considered to be one of the most important technologies ever invented, as it separated communications from live speech, made knowledge preservable, and began the development of numerous devices used for writing and materials to write on.

In many cultures, handwriting is so tightly related to the person writing a text that many consider someone’s handwriting style to reflect either the personality of the writer or his/her emotions at the moment of writing (and also his/her age).

Ink Trap

Sponsored by Blaze Type . Typeface in use: Area Normal Inktrap , designed by Matthieu Salvaggio, 2021.

(Read More)When printing technology was primarily based on printing inked metal types on paper, ink could easily spread into the small corners of the characters. In printing, this effect is called a “bleed.” Especially at small sizes, too much ink spread can weaken legibility.

One of the best examples of a typeface solving the ink-spread problem is Bell Centennial, designed by Matthew Carter in 1975 for the US telephone company AT&T. It needed a typeface for its phone books, which would be printed on thin and porous paper. The resulting typeface featured inner corners that dug into the letterforms’ usual contours. Those are called ink traps.

In digital typeface design, designers still use ink traps, especially for typefaces intended for small sizes (on printed and/or digital media), but also as design features (which can be pretty wild!).

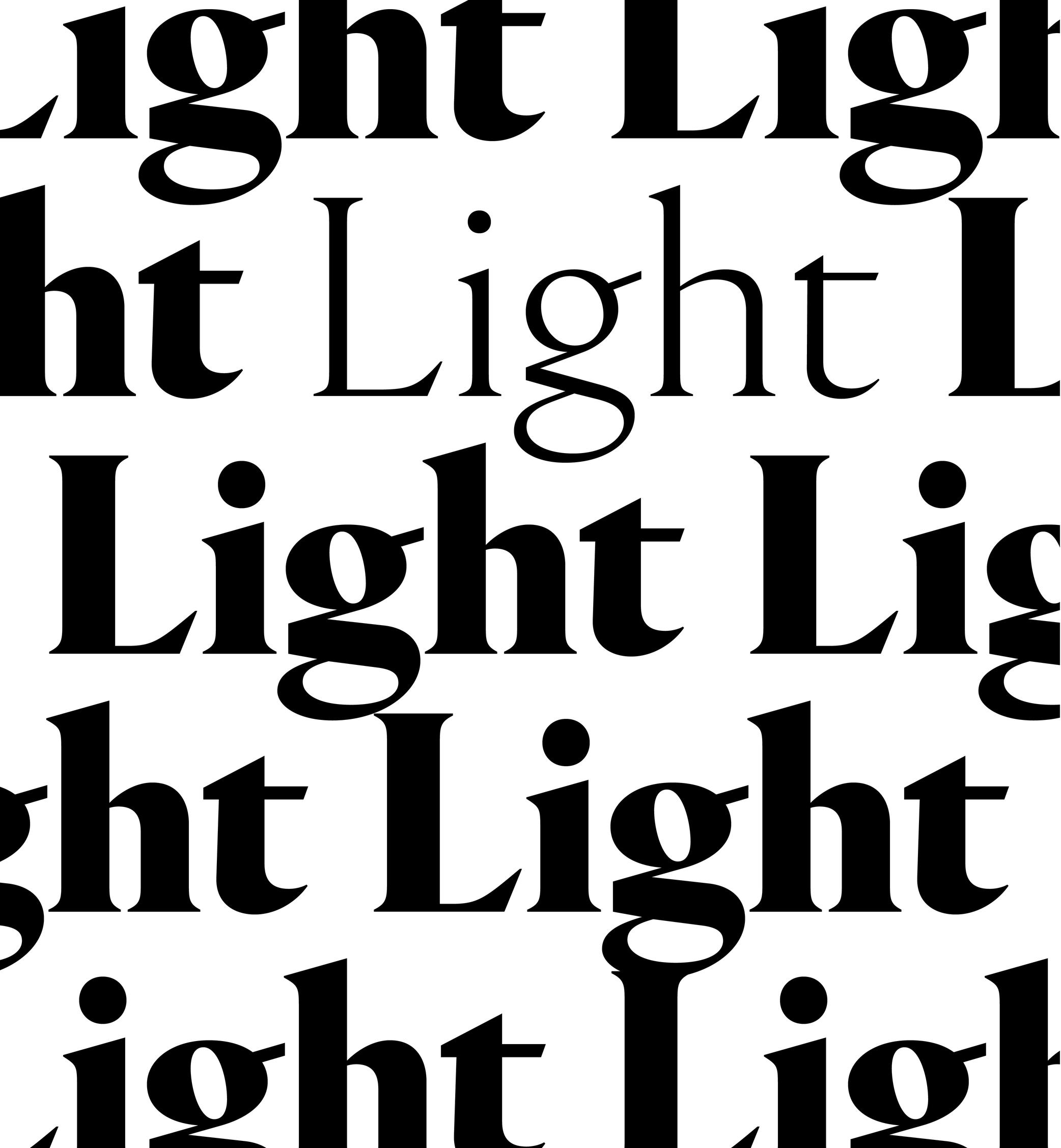

Italic

Univers, extract from Manuel Typographique, by Fournier le Jeune, 1766, as displayed in De Plomb, d’Encre et de Lumière, Essai sur la typographie & la communication écrite, C. Peignot and G. Bonnin, French National Printing Office (Imprimerie Nationale), 1982

(Read More)DESCRIPTION

Two construction styles are possible for the same weight in a Latin script typeface: Roman (or upright) and Italic. Italics usually have slanted letterforms, with more or less obvious influence from handwritten letter structure (connected letters) and shapes (softer starts and endings). In general, italic letters also have a slightly narrower width than their upright companion.

For italic styles to be visually linked to an upright version, they have to be related to each other (similar weight, height, etc.). However, they also need to be different enough so that the reader can easily differentiate one from the other. Managing a good balance between differentiation and similarity is part of the typeface designer’s expertise to design a “nice couple.”

HISTORY

During the Renaissance in Europe, when the Humanist movement emerged, they developed a new style of handwriting that combined the old Carolingian Minuscule (all lowercase letters) with forms inspired by Ancient Roman inscriptional lettering (Capitalis Monumentalis). Both have a close relationship to the ‘natural’ movements of the human hand.

While Humanistic handwriting could use either roman (upright, interrupted) or italic (slanted, connected) letterforms, each direction would eventually become an independent style used for different purposes, as is familiar today. The names we use now also come from that era, with ’roman’ referring to the alphabet of the Ancient Romans and ‘Italic’ being a moniker English writers used to refer to the style of connected letters that had originated more recently in Italy.

In typography, the first italic typefaces used date to around 1500. However, it was not until the mid-16th century that French printers began using roman and italic styles as we do today. They employed both styles in various applications to convey different impressions (emphasis, comments, etc.).

USE IN TYPOGRAPHY TODAY

In text, Italic styles are mainly used as a functional companion for a typeface family’s roman styles.

They are used when a part of a sentence or word needs to be emphasized, or differentiated from the rest. Italics are often used to emphasize titles of various works (albums, books, films, magazines, newspapers, etc.), words in a different language, or words that need to be highlighted.NOTE

Not every writing system uses or even has Italic styles like in the Latin script. Instead, other scripts use different ways to achieve the same purpose of emphasis (i.e., by using a different weight or specific kind of punctuation).

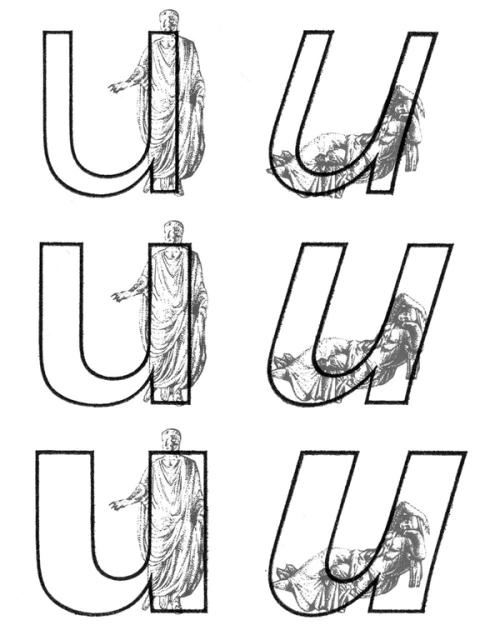

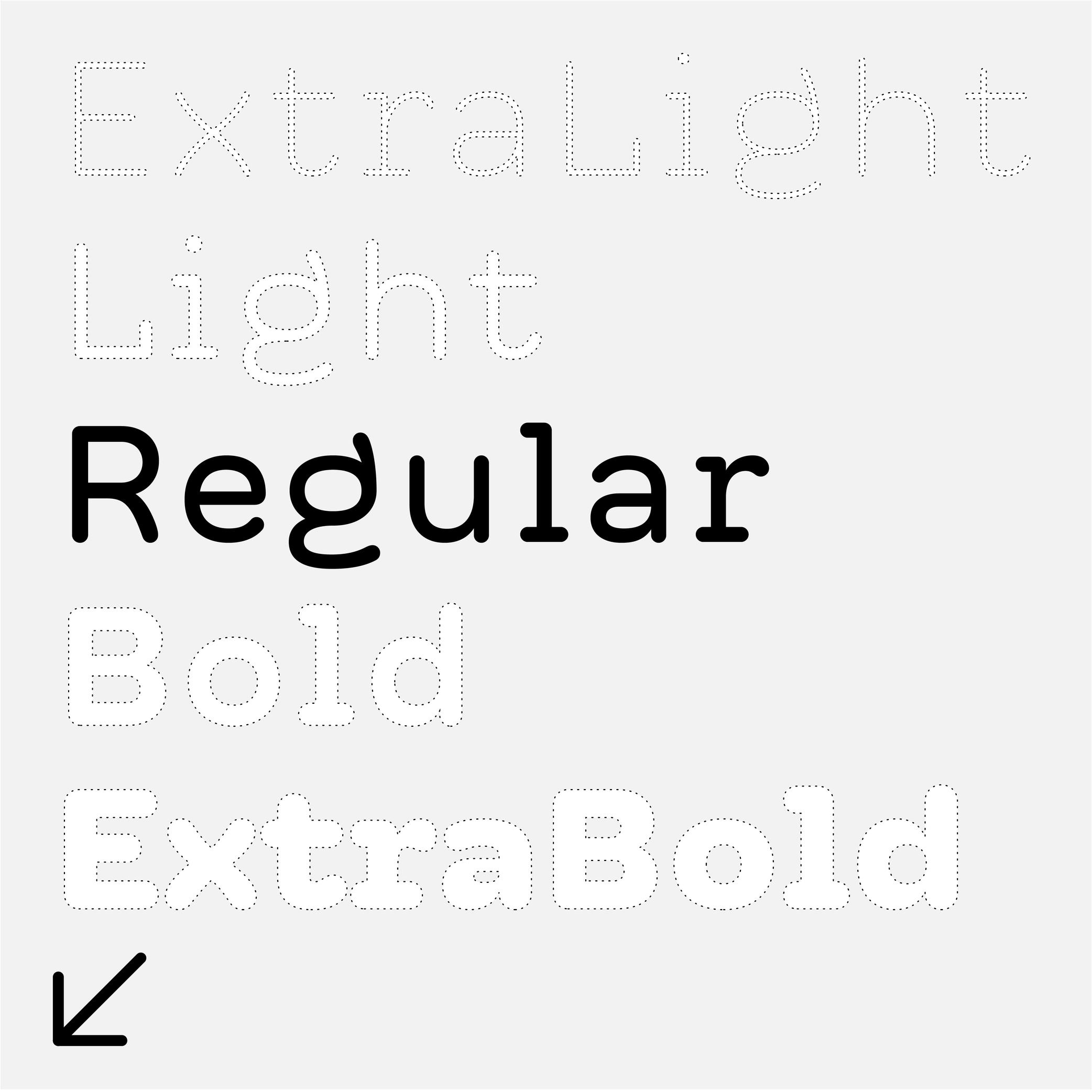

Light (weight)

Sponsored by R-Typography . Typeface in use: Rizoma , designed by Rui Abreu, 2018.

(Read More)A typeface style with a lighter (thinner) weight than the Regular can be called “Light.”

It is one of the most common weights in Latin typefaces (along with Regular and Bold). However, many other terms exist for weight styles on the Design Space spectrum, such as Thin, Book, ExtraLight or Hairline.

Manuscript

Illustration: Malota .

(Read More)A manuscript is a hand-written document.

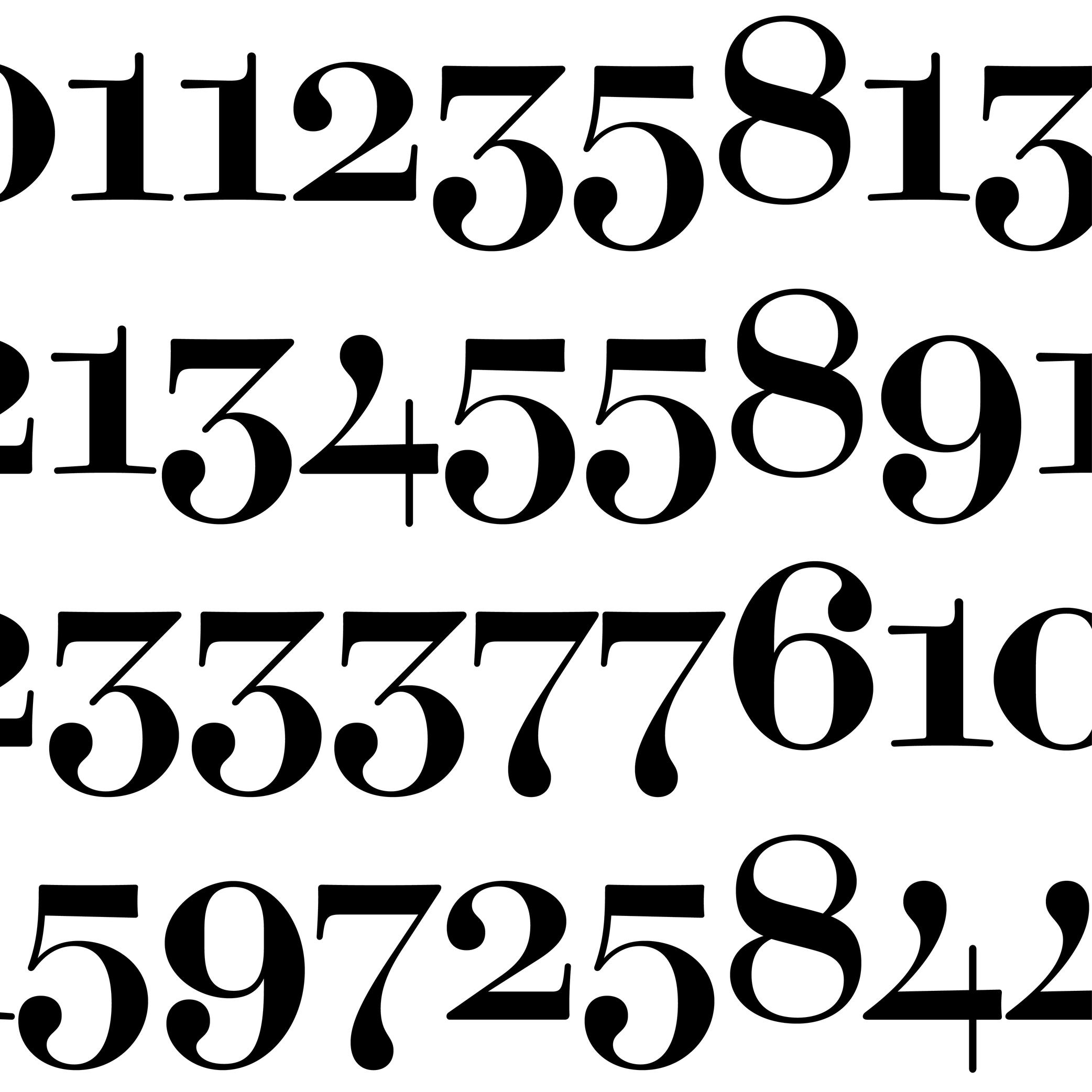

Oldstyle Figures

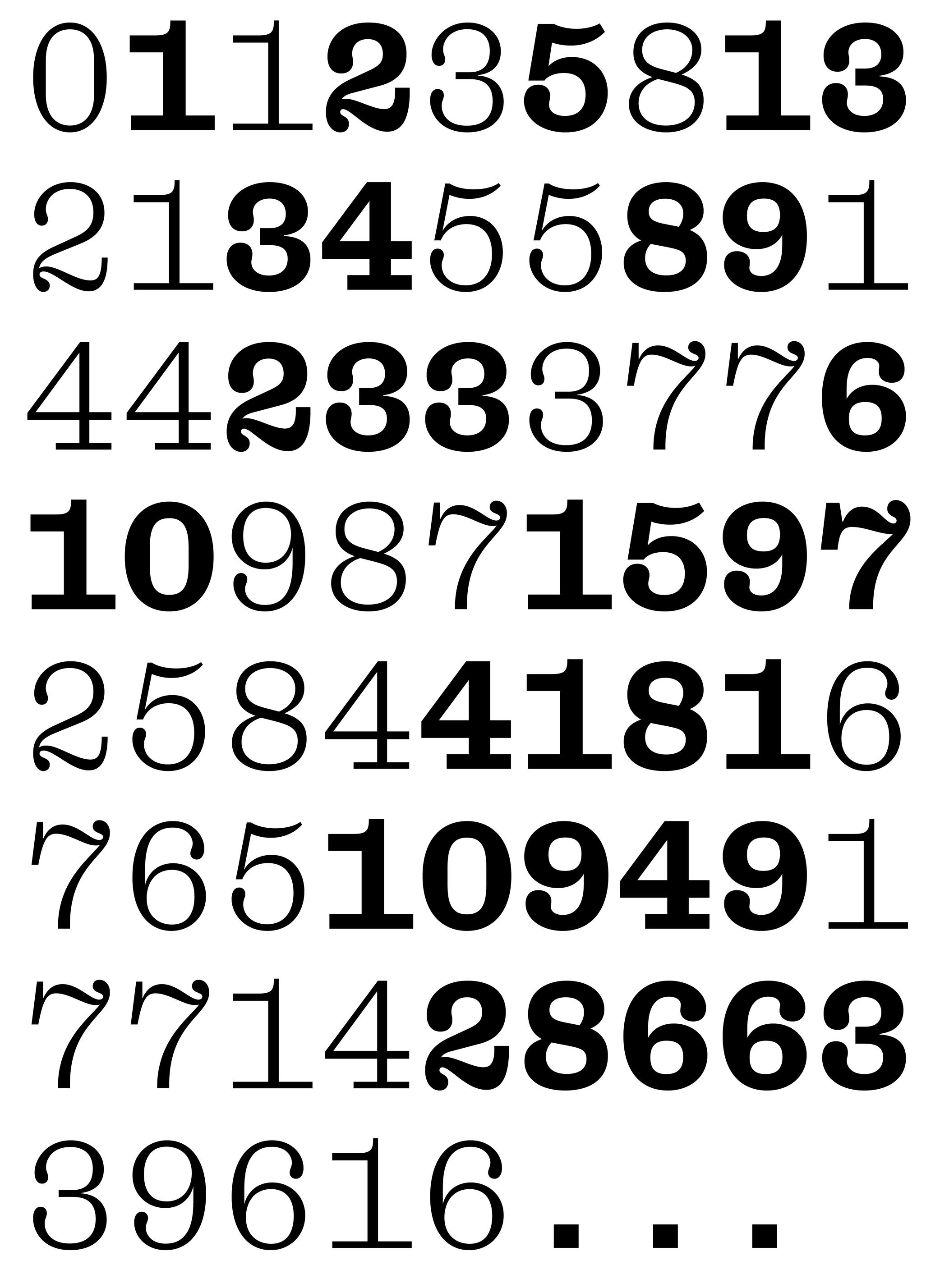

Sponsored by Dinamo . Typeface in use: Daily Scotch , designed by Fabian Harb and Michelangelo Nigra, 2024.

(Read More)DESCRIPTION

Oldstyle figures are designed to fit with the design of lowercase characters. They are more often used in texts as they visually blend in better than the other figure variants.

HISTORY

The proportions of oldstyle figures are closely related to how they were written in calligraphy using similar strokes and movements as those of the (lowercase) letters.

“Oldstyle” used to have a typographic meaning of its own. It was a 19th century/early 20th century term for revivals of Renaissance serif faces after British printers got bored of Bodoni/Didot/Scotch/etc., and particularly referred to revivals of types those from Venice, Paris, and Caslon’s much later roman. Some typefaces had “Old Style” in their name to signify this.

EVOLUTION

Oldstyle figures are also called “traditional” figures in some languages, as more modern styles came later on (hence the name identification) as better adapted forms to specific situations: tabular, lining or proportional figures. In digital typefaces, several style sets of figures are available and can be accessed via the alternate sets.

Regular (weight)

Sponsor Word of Type and feature your typeface in this card with a linked caption. Contact us for more information.

(Read More)Regular weight is the most frequently used style in a typeface family.

With its proportions and features designed to be easily read, it is the best style to be used in running texts.Reversed Contrast

(Read More)

(Read More)The contrast is the relationship between a glyph’s thick and thin parts.

The variation in a stroke’s thickness comes originally from handwriting and results from the writing tool’s reaction to the medium, in combination with how the toll is held and the movements the writer makes. Nowadays, in type design for the Latin script, we refer to a vertical contrast when the vertical parts are thicker than the horizontal ones, which is its “natural” contrast. And the opposite is known as a reversed or inverted contrast.

But these concepts only apply to scripts that evolved using tools and a medium that creates such contrast “naturally,” which is not universal for all. For example, the Hebrew script’s contrast would naturally be distributed the other way around.

Revival

(Read More)A revival refers to a new typeface whose letterforms are based on historic models. Today, when we speak of revivals, we usually refer to digital typefaces that take their designs from existing ones. Most often, they base their forms on exisiting typefaces cast in metal, engraved into word, or produced for photo-composition.

The oldest revivals were made by 19th century type foundries when they adapted early 18th century typefaces for industrial printing conditions. In the 20th century, more revivals from mechanical and photo-typesetting device manufacturers followed.Inevitably, the design of a revival contains unique details of the designer, from interpretations of the initial design while analyzing printed results on paper to those on screen at various resolutions. Today, we can see multiple typefaces designed as revivals from one and the same typeface, but each have (sometimes very subtle) differences. For example, we can think of the many versions of the Garamond.

A revival from a running text typeface is considered as a good assignment for students starting to learn typeface design, as this allows to get more familiar with styles considered as “conventional” before experimenting further with more creativity.

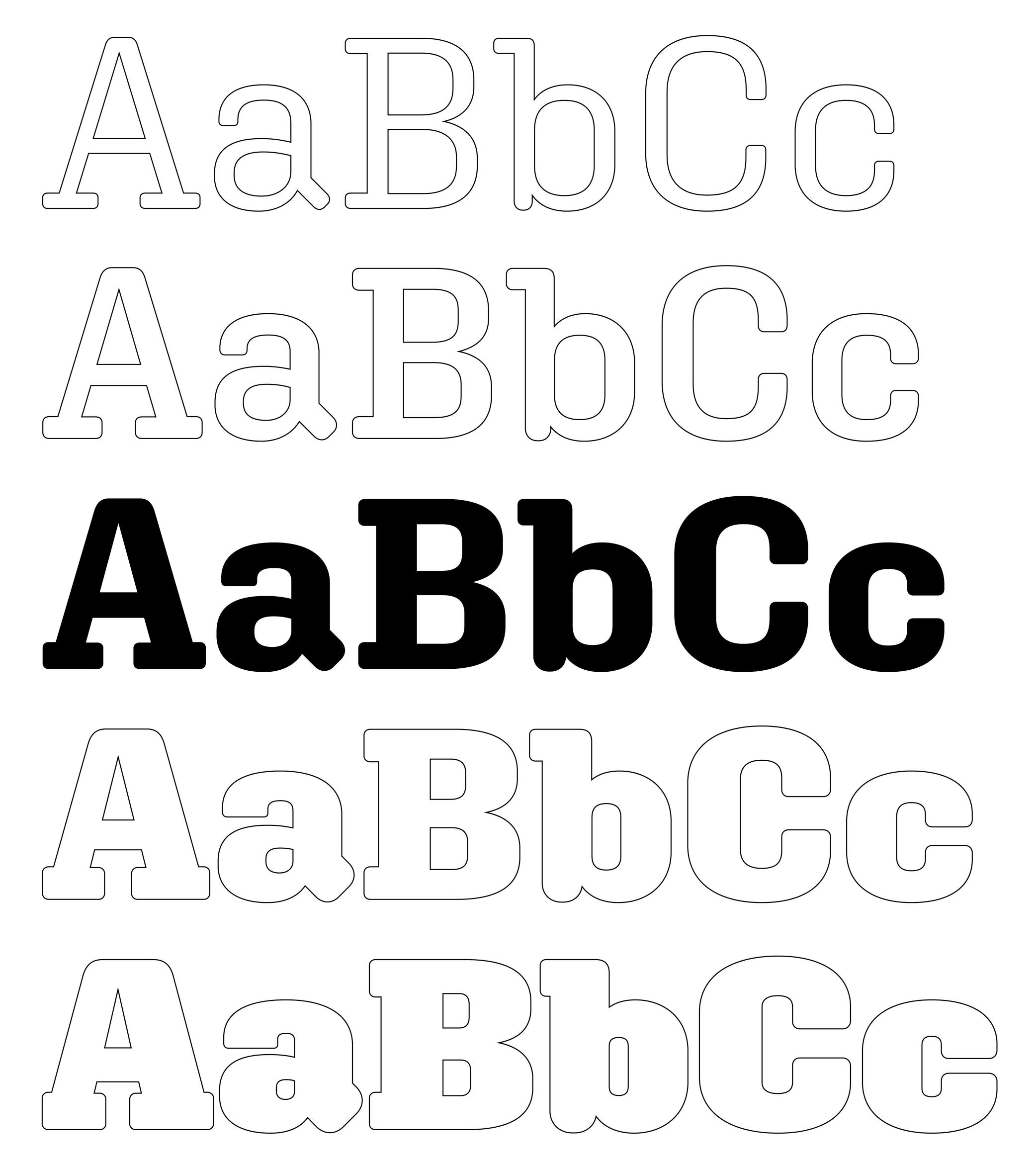

Sans Serif

Illustration: Pauline Fourest (Spaghetype ).

(Read More)DESCRIPTION

Sans serif, or Sans (literally meaning without in French), describes a typeface style without serifs.

HISTORY

As far as we know, the first published sans serif typeface, Two-Lines English Egyptian by William Caslon IV, was published in 1816 in London, England.

Many terms have been used to speak of a sans style as we understand it today, with multiple categories names in different typographic classification systems of Europe: ‘grotesque’ (France and United Kingdom), ‘Grotesk’ (Germany), ‘gothic’ (USA), ‘linéale’, ‘bâton’ or ‘antique’ (France).EVOLUTION

In Europe and North America, Sans-serif styles became popular in the early 20th century as part of a modern trend. Typeface designers experimented a lot around the this style, with some becoming references, and later style sub-categories of Sans-serif: humanistic sans, geometric sans, grotesque or gothic, etc.

But these don’t apply to other scripts that evolved on an independent path from the ‘Latin’ world. Chinese Hanzi have a category of style similar to Sans, called Heiti (or Hei), that doesn’t have as many sub-categories.

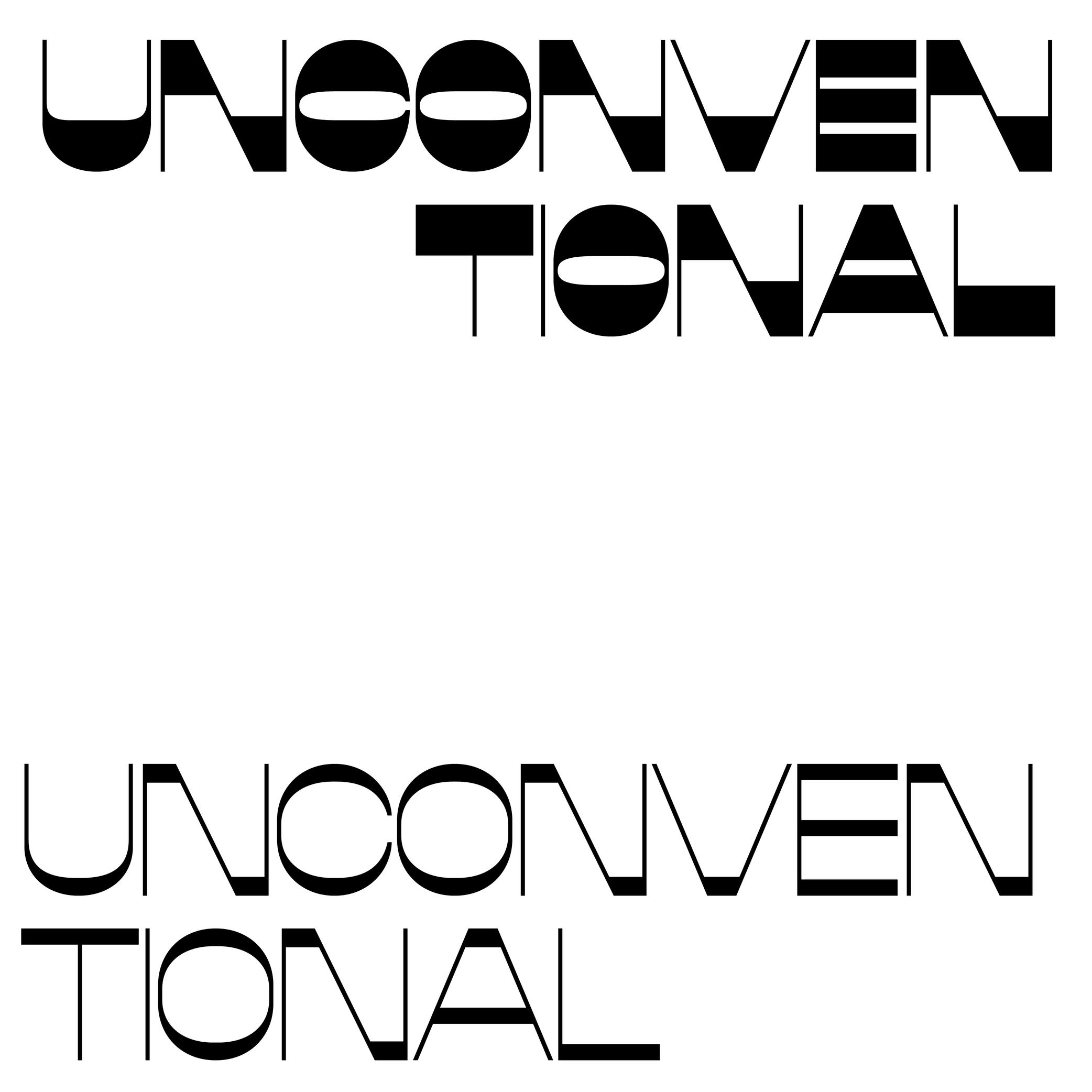

Script (style)

(Read More)DESCRIPTION

Script is a category of typefaces that imitates handwritten forms.

HISTORY

Various categories of typeface styles started to be identified from the various metal typefaces being produced for movable type printing. Metal type technology worked so that each piece of metal representing one character could be assembled and reassembled in every possible combination, meaning that each character was designed as a disconnected form.

As new typeface designs kept being produced (mainly in Europe), more flourished styles for more diverse choices started to appear, especially during the early 20th century. Not only did they give more possibilities for typesetters (for advertisements or novelty), but new typefaces were also a way for type foundries to display their capabilities in technical and design innovation. Beyond italic styles, typefaces that could imitate handwritten forms (with connected and/or irregular forms) were one of the most challenging styles at that time, technologically speaking. As one (early but not the earliest) example of such a challenge, we have the typeface Mistral, designed by French typeface and advertiser designer Roger Excoffon in 1953 for Fonderie Olive.

EVOLUTION

Thanks to the possibilities offered by digital fonts, which have far fewer physical constraints than metal types, the same glyph can have multiple variations and replace one glyph to a more fitting one (see Opentype features or Alternates), to create the impression of handwritten words. Today, there is a wide choice of Script style typefaces, with a high variety of styles (and qualities).

IMPRESSION

Script typefaces are mainly used as display styles, in titles, short texts, or even in brand logos.

They can convey all kinds of impressions from the many possibilities of ‘sub-styles’. Note: script typefaces are not to be confused with lettering!Serif

Illustration: Raven Mo .

(Read More)DESCRIPTION

Serifs are elements at the tips of strokes in serif style typefaces.

HISTORY

The origin and evolution of serifs differ in different scripts and don’t even exist in others.

For the Latin script, serifs come from the combination of the movements of the brush when writing Roman capital letters (the origins of the Latin alphabet) and stone carving techniques.EVOLUTION

Calligraphy, metal and wood type printing, photo composition, typewriters, digital typefaces, all of these tools and techniques contributed various shapes and presence (or absence) or serifs among the various typeface styles that we see today.

The positioning of serifs in each letter has been defined by the writing ductus combined with the tools use. For example, the general rule is that serifs should be on both sides at the top and bottom of vertical stems for upright letters, and none on the bottom of italic stems.

There are multiple possibilities for the shapes of serifs: thin, thick, long, short, wedged, squared, triangular, etc. Many typeface styles have a particular serif shape as part of their characteristics.

IMPRESSION

In Latin script, different impressions and feelings are associated with specific typeface styles (traditional, luxurious, casual, elegant, etc.), which are mainly due to the circumstances of their creation, usage preferences, and habits.

For example, humanist or transitional serifs are the go-to styles for long reading uses.DESIGN

For styles where serifs are on both sides of the stems, some asymmetrical letters (such as f, r, F or P) have a large opened counter on one side. To compensate for the imbalance created by the “empty space”, the designer can adjust the serif on that side by making it longer.

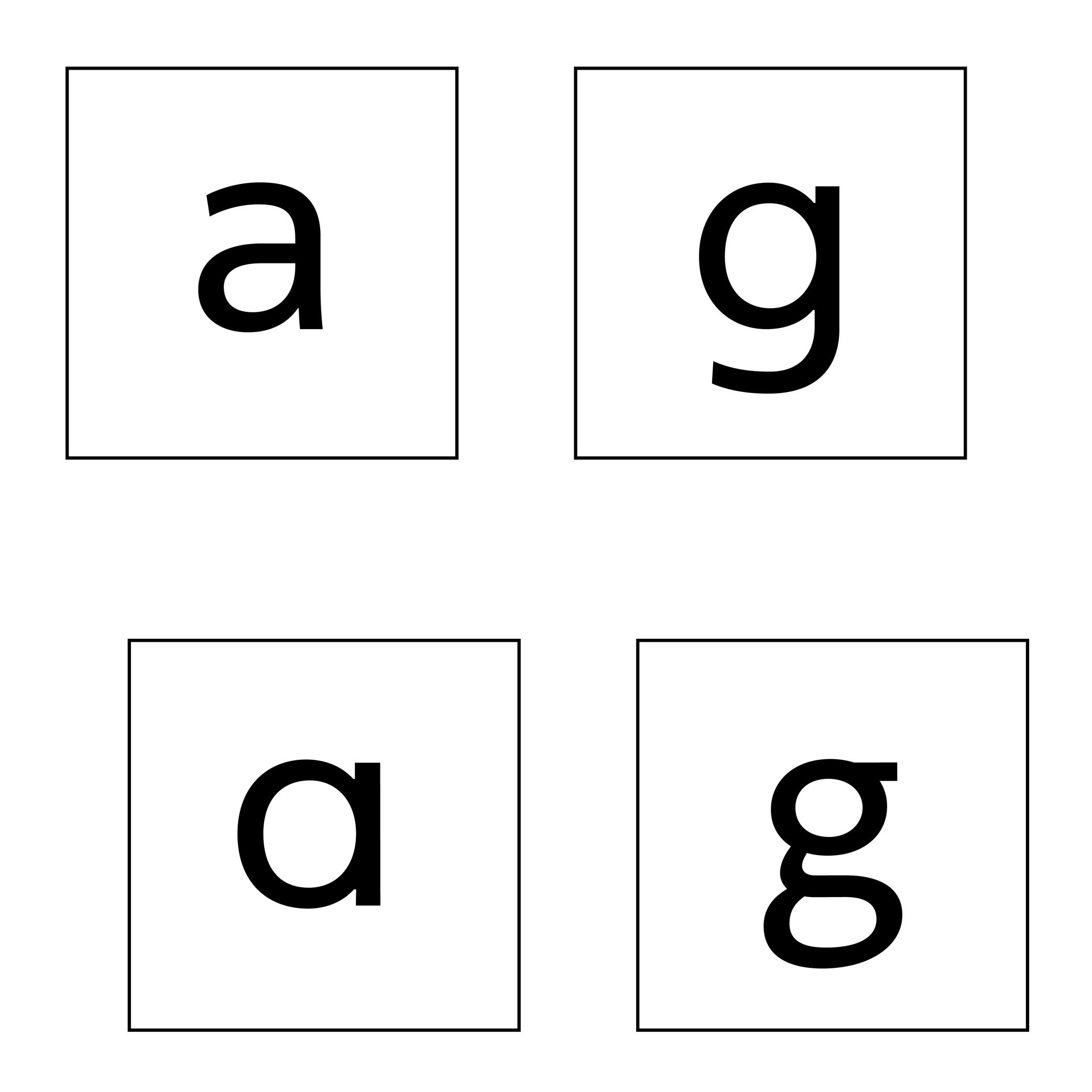

Single or Double Storey

Sponsored by Typotheque . Typeface in use: Zed Text , designed by Peter Biľak, 2024.

(Read More)Latin letters a and g can be represented with two different constructions:

- single storey, for modern and/or geometric styles;

- double storey, for traditional and/or classical styles.

In some typefaces, both constructions are available, as designers feel that some users prefer one over the other.

The letter g can also be designed with a half storey construction, often seen in Scandinavian designs as a legacy from Danish street signs.

Style

Illustration: Pauline Fourest (Spaghetype ).

(Read More)In any writing system, typefaces exist in an infinite number and variety of styles. They are influenced by many factors, such as technology, tools, necessity, and trends. But some of them are (or can be) grouped into categories for their similarities, into classification systems (sans serif, serif, humanist or geometric, etc.).

In the Latin script, we also identify Roman (or upright) and Italic as two ‘companion’ styles of the same typeface style.

Swash

Sponsored by Blaze Type . Typeface in use: Sigurd , designed by Matthieu Salvaggio and Léon Hugues, 2021.

(Read More)Swashes are the elongated extensions of letters, designed with longer strokes than their “usual” construction, most generally as a decorative feature and/or in display style typefaces.

HISTORY

They appeared during the metal type era in the Latin world, when swashed letters served as decorative features to the text. They were also a way to showcase the punch-cutters’ skills, sometimes with incredibly long and elaborate swashes.

Swashes still have the same purpose today in digital typefaces, where “normal” letters are the default ones and swashes can be activated as alternates from the typefaces’ features (if available).Tabular Figures

Sponsored by Dinamo . Typeface in use: Daily Slab , designed by Fabian Harb and Michelangelo Nigra, 2024.

(Read More)Tabular figures are designed to fit in the same uniform width frame, making them suitable to be used in tables, and this helps identify the numbers more easily and clearly.

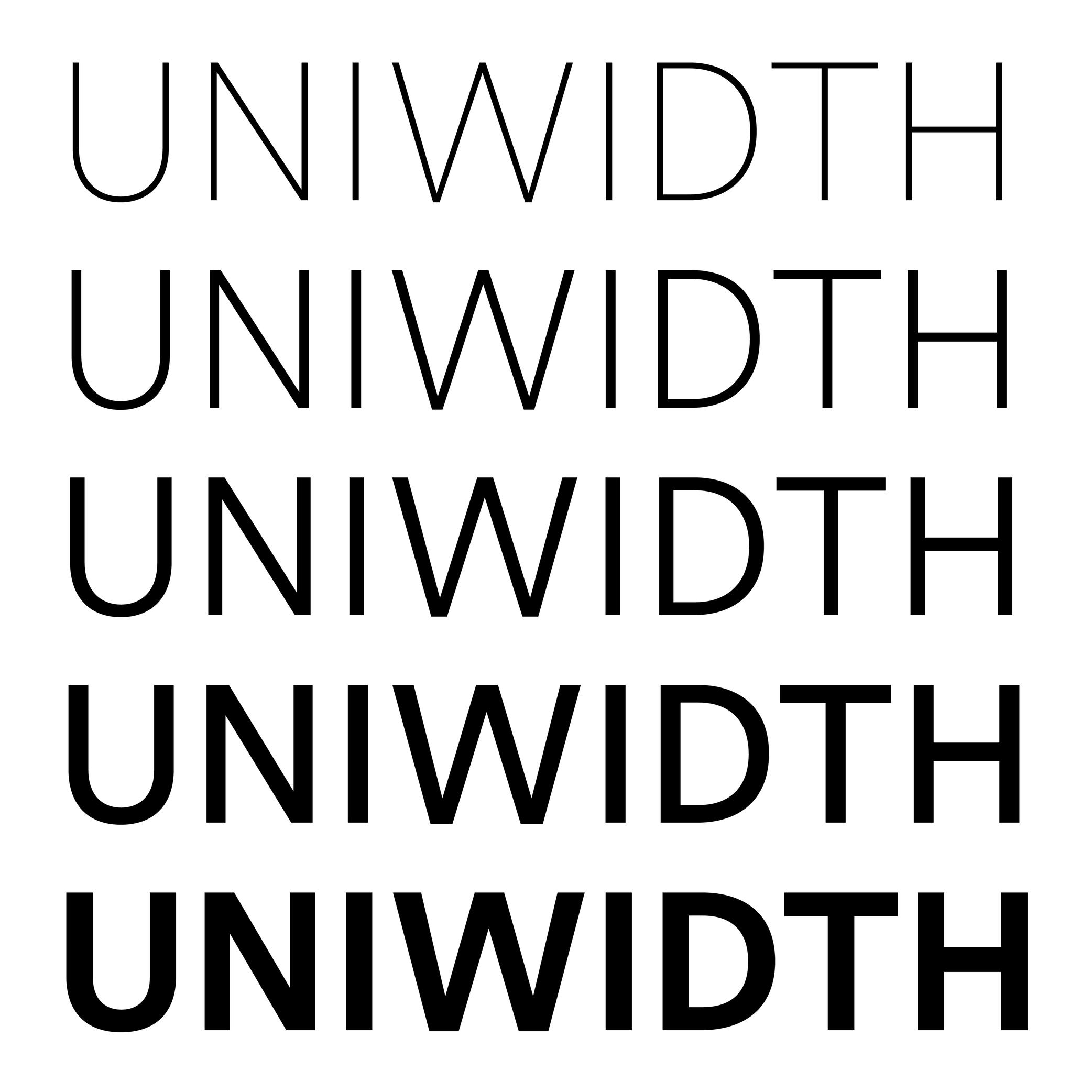

Uniwidth

Sponsored by Frere-Jones Type . Typefaces in use: Retina , designed by Tobias Frere-Jones, 2016.

(Read More)ALSO CALLED

Multiplexed or Duplexed.

The term (in English) was brought up by Armenian and American type designer and teacher Hrant Papazian. Many people are still debating about which naming to choose...

In type design, the width and/or spacing of a glyph often changes depending on the weight or style to maintain visual balance. Uniwidth typefaces, however, keep the same horizontal metrics across all weights and styles of a family. It is not the same as monospace fonts, for which all glyphs share the same width—duplexed typefaces are still proportional.

This consistency facilitates digital typesetting, particularly when text changes in style dynamically (e.g., on hover or in interactive interfaces) without altering the layout.

Variation Axis

(Read More)

(Read More)A variation axis allows a continuous interpolation of outlines between at least two compatible sources (also called masters).

It is a trajectory between different states of a given shape. For example, the weight axis would shift points to adjust the stem thickness, allowing a transition from Thin to Bold styles.FONT ENGINEERING HINT

The OpenType Specification defines 5 standard axes: weight, width, optical size, italic, and slant.

Note that italic acts as a stylistic link between two styles rather than a true interpolation axis.

These guidelines serve as a reference for how axes should be implemented into a font.Variation axes are stored and referenced across several font tables:

• avar (Axis Variations): normalizes axis coordinates

• fvar (Font Variations): provides location coordinates for the instances

• STAT (Style Attributes): provides human-readable names for axes and their defined instancesWeight

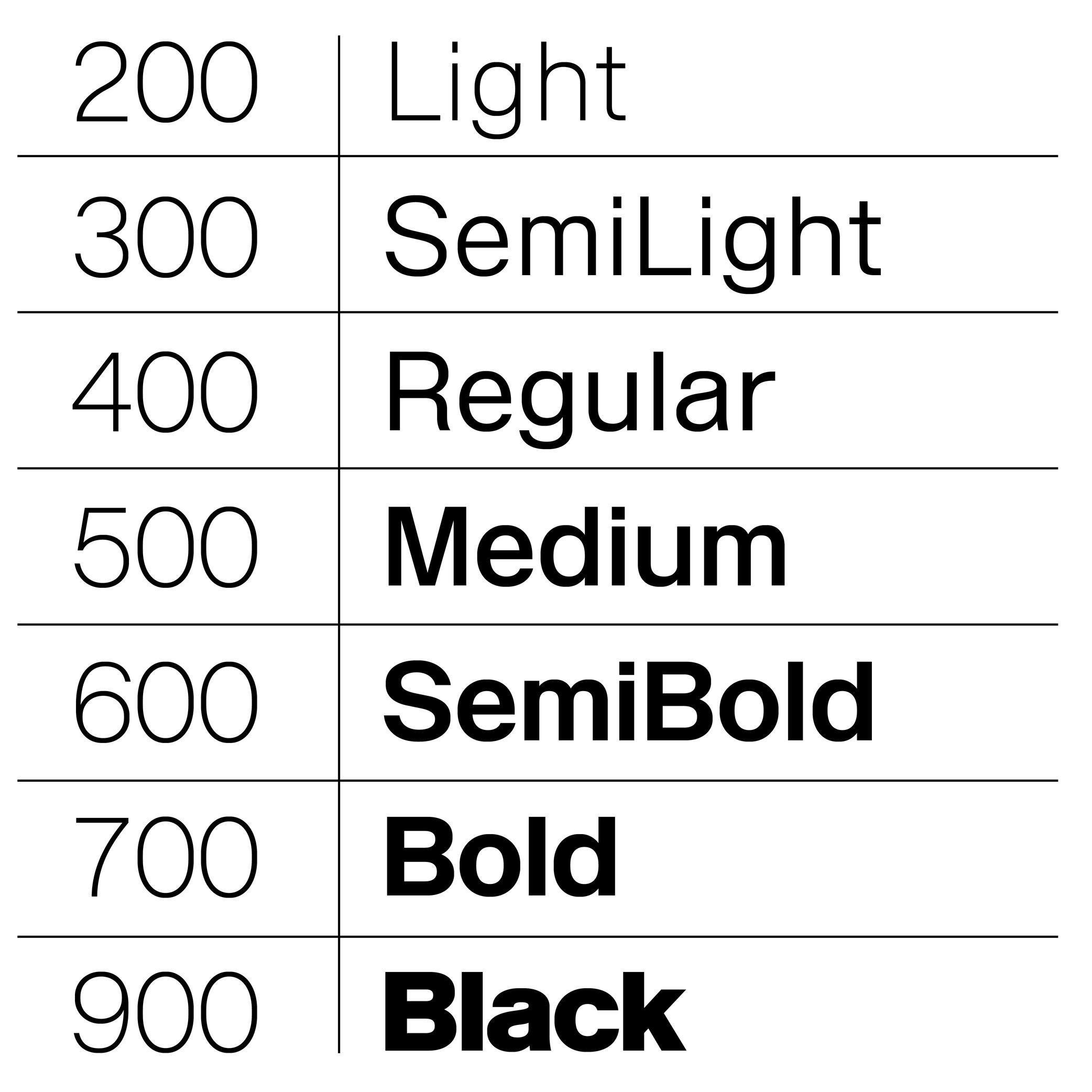

Sponsored by Production Type . Typeface in use: Enduro , designed by Emmanuel Besse, 2020.

(Read More)The weight of a typeface refers to the thickness of its strokes.

Within a typeface family, different weights are designed to be visually consistent across all glyphs of a given style.

NAMING CONVENTIONS

While much of the historical naming conventions (e.g., Light, Bold, Black) originate from the Latin typographic tradition, the concept of weight applies to all writing systems that use stroke thickness variations. These labels are not universal standards as style description conventions differs from a culture to another.

WEIGHT NAMES & CSS VALUES

In digital typography, weights are also expressed numerically, using the “font-weight attribute”:

• Thin: 100

• ExtraLight: 200

• Light: 300

• Regular: 400

• Medium: 500

• SemiBold: 600

• Bold: 700

• ExtraBold: 800

• Black: 900FONT ENGINEERING HINT

In OpenType font formats, weight is stored in the OS/2 table under the “usWeightClass” field, which maps to CSS “font-weight” values (ranging from 100 to 900):

• while CSS defines nine steps, “usWeightClass” allows values from 1 to 1000, giving finer granularity for internal font definitions;

• CSS weight values are expected to correspond to the font’s weight class. Following this standard is important because many environments rely on these mappings for text rendering and style linking. If, for example, Regular = 350, browsers or apps may mislabel it or fail to recognize it as Regular, causing user confusion or incorrect transformation to Bold.For variable fonts, the weight axis is defined by the registered axis tag “wght.” Unlike static fonts, it supports continuous interpolation between a minimum and maximum, allowing CSS “font-weight” to take any integer (e.g., 347) within the supported range for smoother transitions and precise control.

Localized weight names (e.g., ‘Gras’ for Bold in French, ‘Fett’ in German) are often generated from the OS’s internal dictionaries. This ensures style names appear in the user’s language even if the font lacks explicit translations. If the default naming does not strictly follow OpenType Specifications, localized names may not be translated correctly.

Width

Sponsored by Blaze Type . Typeface in use: Surt , designed by Matthieu Salvaggio, 2020.

(Read More)Other than the width of individual glyphs and characters (the letter M is usually wider than I), there are also various widths for typeface styles that participate in its personality or help make a content set in a specific width to fit specific conditions.

Some common width styles are: Narrow, Condensed, Regular, Extended and Wide. They serve more as a way to identify each style within a typeface family, rather than standards to follow for all scripts, as they can be different from one script to another.